“He’s a builder, he’ll just know how to build it.” This was the response Tabitha Binding, Head of Education and Engagement at Timber Development UK, received when supporting a winning group of student architects to make their successful timber-framed concept an installation reality at the London Design Festival.

Yet when Tabitha sat down with the architects and expert carpenter enlisted to build the installation, they found they were all talking a completely different language.

The architects were communicating with 3D software, while the carpenter, using pencil and paper, was seeking to understand how the dimensions met to ensure the structure would be supported correctly. Through collaboration, help from other timber trade experts and hands-on experience during the installation’s construction, all parties shared their knowledge and the communication barriers disappeared.

Encouraging education and engagement around the use of timber in construction, as Tabitha’s job title suggests, is exactly what her role is all about. During this interview, we discover why we need to educate and upskill the students of today, who will become tomorrow’s specifiers, designers, engineers, project managers, quantity surveyors and contractors. We need everyone to understand how to use timber wisely if we are going to create a future full of low-carbon timber construction.

What is your role and why is it important for timber construction?

I work with industry, professionals, academia, and students to enthuse, encourage and educate – to increase knowledge and competency in timber as we transition to a biobased economy.

With 5,000 architecture and 5,000 engineering students entering the world of construction and the built environment every year, business as usual is no longer an option. We have to change the way we build to create a low carbon, sustainable future.

We spend our lifetime in buildings and most of our money on our homes. And yet, while architecture and engineering are viewed as ‘suitable’ career choices, construction itself often isn’t, despite its vital importance to the UK economy. Let’s face it, without construction experts to build our homes and buildings, we’d be pretty stuck.

The most impactful decisions on carbon emissions in the built environment are made long before the foundations of a building are laid down. They happen in architects’ studios, within the offices of city planners, and in the engineering space. Decisions made during the project development phases impact both operational and embodied emissions, as well as how residents will live and work in these structures.

My role is to bring the design and delivery disciplines together to build better and understand more clearly the purpose of each building, to give everyone pride in their work and stimulate mutual respect across the timber construction supply chain.

What are the main roadblocks to creating low-carbon buildings in the UK?

One of the key roadblocks has been the educational gap around timber, which often features as little more than a day of learning and coursework within some universities. Departments can be disparate with scant collaboration across the built environment subjects, and some less progressive universities are even still teaching outdated methodologies. As a result, many students simply don’t know any better. Many also don’t have any hands-on experience that can contribute to a more rounded and knowledgeable approach to timber construction.

This means graduates emerge without the knowledge, ability, or confidence to employ timber systems. With our University Engagement Programme, we are seeking to change this – and make timber systems and technologies a core pillar of any built environment course in the UK.

What other initiatives are you implementing to overcome the timber-related education gap?

An important part of what I do is delivering project-based learning that breaks down barriers between professions, and facilitates dynamic learning and practical, transferable timber skills.

One way we do this is by running interdisciplinary challenges where Timber Development UK (TDUK), the now amalgamated Timber Trade Federation (TTF) and Timber Research and Development Association (TRADA), hosts a workshop based on a real-life project.

For example, the one we did just before lockdown was sponsored by timber industry partners and saw 58 students from universities across the UK gather at Cardiff University and compete to design, cost and engineer the best low-carbon, energy and water efficient timber community housing in less than 48 hours.

Each team consisted of student engineers, architects, architectural technologists, quantity surveyors and landscape architects, and received hands-on support from pioneering design professionals and industry members, including judges from Mikhail Riches, Cullinan Studio, Stride Treglown, Ramboll, BuroHappold, Entuitive, Gardiner & Theobald and PLAN:design.

How is the STA supporting your quest?

Last year’s competition Riverside Sunderland University Design Challenge (RSUDC21), saw 300 students design, engineer, plan and cost a three-bed family home along with an indicative masterplan for 100 homes to meet RIBA2030 Climate Challenge targets – with low-carbon timber and timber-hybrid systems providing the main material focus.

The STA’s chief executive, Andrew Carpenter, spoke directly to the students during the weekly Friday ‘virtual catch up’ session and enabled access to the STA’s vast information library whilst the Association’s Technical Consultant also supported the event, delivering a webinar on timber and fire. They were among 78 professionals who participated across a 12-part webinar series, which proved to be a unique and ambitious learning opportunity for the whole industry. Experts presented on everything from sustainable timber and offsite manufacturing, counting carbon, timber challenges and structural engineering to how you cost and budget timber to post-occupancy evaluation – the webinar series is still available as a learning asset on YouTube.

Are there any specific hotspots in the timber supply chain that you’re focusing on going forward?

Yes, definitely. One hotspot is the point at which design and construction meet. Tackling this collision proactively, I’m currently working strategically with New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering (NMITE) as its Centre for Advanced Timber Technology (CATT) Lead for External Engagements and Partnerships to deliver training that encourages greater design and construction collaboration across the supply chain.

We’re looking to develop some short courses and CPDs into a longer Bachelors degree in Sustainable Built Environment over the next year and, starting in September 2022, we will be running some interactive education days that will bring together the whole supply chain.

These will invite architects, engineers, clients and cost consultants, contractors and timber industry supply chain experts, such as offsite frame manufacturers, to up skill, reskill and address topical industry issues. Topics on the table embrace everything from level foundations to air tightness and energy performance and, of course, tackling the reduction in carbon at element, building and operational levels. Allowing people to exchange really good knowledge and encourage more collaboration will ensure that where we build with timber, we also build better with timber.

How did you find yourself in the timber industry?

I started out aged 17 working with coppiced hazel and softwood thinning. My first engagement with the timber construction industry was when I joined the Welsh timber charity Coed Cymru Cyf in 2010. The charity focuses on creating and managing Welsh woodlands for multiple benefits.

From there I was involved with ‘Tŷ Unnos’ – literally translated as ‘a house in one night’. The name was chosen to convey a fast and adaptable building system making use of local material and local labour, all based around Welsh timber. It led to the development of a fully certified volumetric offsite system, where buildings left the factory fully finished and fitted. That’s when I got involved with post occupancy evaluation, design for manufacture and assembly, plus disassembly & reuse and the Passivhaus energy efficiency standard.

I’ve also worked on European technical guidance, thermal modification of Larch for joinery with Bangor University, a Wood Encouragement Policy with Wood Knowledge Wales, which was adopted by Powys County Council in 2017 and, more recently, joined TRADA in 2018 to focus on education and engagement in universities. The rest, as they say, is history!

Do you have a takeaway message for the industry?

Absolutely. It’s all about collaboration early on. If we work together across disciplines we will have more fun, be more productive, less wasteful and create better buildings that are both energy and resource efficient and beneficial to human and planetary health.

To join in, keep an eye on the new Timber Development UK website for the collaborative opportunities arising when we launch in September. https://timberdevelopment.uk

Connect with Tabitha Binding on LinkedIn

The STA echoes this collaborative approach, working closely with members, stakeholders and the UK construction industry to address the issues that timber construction faces. The STA’s mission is to enhance quality and drive product innovation through technical guidance and research, underpinned by a members’ quality standard assessment – the STA Assure Membership and Quality Standards Scheme.

For more information visit: https://ttf.co.uk/

Stewart Dalgarno is the Director of Innovation and Sustainability at the Stewart Milne Group, one of the UK’s largest independent award-winning housebuilders. Here is his thinking as to why now is the time for timber.

How do you develop your expertise in timber construction?

I developed my expertise in timber construction through working with the Stewart Milne Group for the last 38 years, as a house builder and as a timber frame manufacture. During that whole career I have lived and breathed timber frame construction, at the core of what we do, as a residential house builder.

What are you such an advocate for the use of timber in construction?

I am an advocate for the use of timber in construction because I just think it is the right thing to do from a sustainability point, but commercially, from a profit point of view, it is the most valuable commercial, attractive, simplest way to build homes. For the last 30 years we’ve been using timber construction and we would not be in the place we are today without using timber.

How has the industry changed in the time that you have been involved?

I have seen lots of changes in the industry since I’ve been involved, with the growth in the marketplace for timber frame construction in Scotland – 85% is timber framed. This is my heritage. I’m glad to see in England it has also increased now and will continue to grow. We’ve seen challenges come our way, but we have improved solutions that give us confidence going forward, to see the challenges in net zero carbon. On many occasions we’ve developed net zero carbon homes that will be, I think, something we will be proud of going forward in the future of the industry.

What are the benefits of modern methods of construction (MMC)?

The benefits of MMC are clear in my mind. As a housebuilder we see speed, quality, surety – a build on time – as being critical. Also, we are less reliant on bricklaying and critical skills are short in the marketplace. Using timber frame construction, for us, solves all of that.

Why is timber frame NOT the preferred method for many housebuilders?

The barriers to the uptake of timber construction I think of are just knowledge and sharing of good and bad experiences and learning from that – overcoming some of the perceptions that will arrive in the marketplace. For 45 years we’ve been building timber frame homes. We can get insurance. We can get warranty. We can get mortgages. We have never had a problem in our history of building timber frame homes.

What more needs to be done to increase the use of timber?

There’s more we can do to educate people on timber construction. There are lots of new forms of timber related construction in the market, such CLT (cross laminated timber) mass timber construction. So, more tests…more education…more knowledge centres. More innovation brings confidence in the marketplace, taking people with us on the journey – key people like warranty providers, lenders and insurers. To me that is one of the key things we should be doing more of to encourage more timber being used in the sector.

Can you summarise the benefits of timber for us?

The benefits of using timber compared to other materials for house builders is really the speed, quality, but really the sustainability credentials. We are finding through our ESG requirements nowadays that it is quite important to demonstrate, by using low embodied carbon materials. The fact that we use timber gives us a tick in that box, substantially, straight away.

What is the wider market for the use of timber in the housebuilding sector?

The wider market for timber frame is exciting and it’s progressing quite a lot. We see a lot of new housebuilders coming into the marketplace, small SME type developers, private rental developers, affordable developers and they’re all looking to use smart ways of building homes and really timber frame here is the ‘here and now’ answer for them.

How does timber frame meet the needs of the Government’s ‘Build Back Greener’ strategy?

Timber frame construction meets the build back better, build back green agenda because of its sustainability credentials. The fact there are less skills needed on a timber frame housing site than a traditional site and it’s just viable, so we can all enjoy the economic benefits of building new homes here in the UK.

How have you found your dealings with the insurance industry and what does it need to understand?

We have worked with them for many, many years and we ensure we have got the right standards, right qualities, the right fire tests of the kits and everything you need to technically prove this is a ‘here and now’ proven solution.

How does timber fit with the Future Homes Standard?

Timber fits with the Future Homes Standard very well. One of the key criteria of that is an energy efficient fabric. We have always believed in a fabric first approach, fit and forget, where you have got the insulation within the timber frame wall system and therefore you are reducing the heat load. That allows other technologies like solar panels and heat pumps that then decarbonize your home, to make the Future Homes Standard, to get to a net zero carbon outcome.

What do you think is the future for timber frame construction?

The future for timber frame construction, for me, is to do more in the factory and less on site. We’ve got a good heritage of making things, we can do more in the factory through automation – to put in insulation, put in windows, then maybe cladding, then maybe services. We’re bring a whole house system, a panelised system. We firmly believe it is the way to go. We think timber frame can be at the heart of that future.

Andrew Waugh, Founder and Director at Waugh Thistleton Architects, was part of a recent visit by Construction Minister Lee Rowley MP’s to The Black & White Building. Designed by Waugh Thistleton and owned by The Office Group (TOG), the fully engineered timber building providing premium flexible working space, will be the tallest timber office structure in London. Andrew discusses why the visit was so crucial to the Confederation of Timber Industries (CTI), which is an umbrella organisation representing the UK’s timber supply chain, and with which Waugh Thistleton is in partnership.

Government legislation that promotes the use of timber throughout the construction industry is required in order for the UK to meet its net-zero commitments. However, due to the number of interwoven alliances and systems within the legislation, it’s simply not as easy as taking building materials out and replacing them with another, which poses a big problem. There are also more speculative parts of the industry that present challenges, such as the nervousness and concern surrounding insurance and pricing.

The minister’s visit to The Black & White Building was crucial because it was proof of concept. We were able to demonstrate that timber constructions are cost equivalent to a concrete building, faster to construct, ensure better working conditions on-site and produce a building with a higher financial value. Additionally, landfill waste is minimised and there’s an 80% reduction in site deliveries, which all contribute to more sustainable construction practices. We were able to show the minster what a low carbon construction can look like.

A lot of work around sustainability over the past 20 years has been centred on layering additional systems such as triple glazing, the addition of more insulation, building management systems and mechanical heat recovery, but what we really should be focusing on is making things simpler. Timber buildings allow us to find the beauty in simplicity, and to design sufficiently for the purpose of the building and not beyond, which is something that the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report explores in more detail along with a global assessment of climate change mitigation progress, along with potential approaches to the overall issue.

It is a fact that timber is currently the only viable alternative to steel and concrete, additionally, it is an existing technology with a sophisticated supply chain. We must reduce our reliance on steel and concrete, ideally by reducing the use of both materials by 50% in the next 8 years, and replacing them with timber. As timber is a uniquely replenishable structural building material for high-density urban construction, we have the opportunity to demonstrate a clear alternative way of doing things, by using an existing system to prompt the evolution of construction.

These changes must happen immediately, and in terms of demand and availability, timber is incredibly well-suited to adopt this in a short time span. In Europe, more than half of the trees felled are burned, so we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of the opportunities with timber, and the timber manufacturing industry is growing exponentially. Governments in Europe and North America are changing their changing building codes and adapting legislation to promote the use of structural timber; the UK is unique only in its failure to do so with the same haste.

It was incredibly important for the minister to visit The Black & White Building to get a good look at what the other countries are getting so excited about, which is a technology that was innovated in the UK and exported around the world by UK firms. The time is upon us to catch up and for the UK Government to take the same action that many others have already taken.

To learn more about The Black & White Building, and other Waugh Thistleton sustainable projects, visit: https://waughthistleton.com/practice/

To read about the Construction Minister’s visit to The Black & White Building, visit: https://www.structuraltimber.co.uk/news/structural-timber-news/uk-construction-minister-visits-ground-breaking-low-carbon-timber-building-in-london/

Using the generic term ‘wood’ is analogous to using the word ‘food’. Wood covers an estimated global diversity of over 20,000 woody species of plant. A few thousand of these are commercially used and these are as diverse as the cultures that use them. Wherever we look, the use of wood is deeply rooted in human history and indeed in everything we do today.

When I think of ‘wood’ I think of an ingredient that can be transformed from a renewable material resource into a gourmet feast of colour, texture, and pattern or used simply as a mass-produced component that we order from the builders’ merchant. The designs we dream up sometimes rely on individual trees where we want something special, but we are most likely to rely on standard sawn or Planed All Round Timber (PAR) sizes harvested and converted from forest trees and readily connectable using metal fixings like a Meccano set. Whichever way we use wood we must only specify sustainably sourced timber from schemes such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) to help protect them as a regenerative resource. Thankfully most timber suppliers now endorse these schemes and provide a range of timber products with trusted certification.

There is no other material like wood and it is so easy to use once you have familiarized yourself with its properties and available sizes, which do vary considerably from softwood to hardwood and across the available species. As an architect, this is what makes designing, specifying, making joinery and furniture and especially working with those skilled in the art of woodwork in all its forms, so rewarding.

The versatility of the material is as diverse as its applications. The relative lightness of this material is balanced by its strength and for some species, the ratio of these is better than steel. When exposed as a finish there are exquisite tactile qualities to choose from as well as a softness in light which is so appealing in exposed CLT construction. There are now multi-occupancy buildings where CLT has been used as a wall or ceiling finish – even the stairs and furniture can be made from this material. These advantages of using the wood stem from the connections to the forest that is then recreated itself in the home.

Cutting edge zero-carbon houses need to incorporate as much wood as possible to sequester carbon. This is important as it is the most practical way to reduce or even produce a negative carbon footprint. But the mindset for sustainable thinking starts with choosing the right materials. Foundations can be minimised using light timber framing and by making the most of the engineered timber products available which now play a significant role in MMC. I also see more interest in systems that are hybrid in nature and incorporate steel connections and consider thermal mass to assist with mitigating overheating now that the new Approved Document O must be met. Meeting the overall building physics strategy is essential to futureproof the asset so that it is insurable, mortgageable and comfortable to live in.

Moving up the scale, multi-occupancy mid-rise apartments can be constructed in timber frames or CLT but architects and engineers must understand the material and its possibilities and limitations. A decade ago, when low U-values became central to developers’ sustainability ambitions and Approved Document L of the Building Regulations cranked up demands for lower U-values, the Structural Timber Association (STA) began to develop new high performance-tested wall, floor and roof types to address this. These now form pattern books available for download on their website.

Architects’ demands on timber frame-based building systems must now change to align with the requirements of the Building Safety Bill. Design teams are now expected to demonstrate that they have the relevant experience and expertise to design buildings and are expected to use comprehensively tested systems and to pass Gateway 2. No home should be built unless it is constructed safely and competently and, of course, can be maintained as such thereafter. This is foremost for the protection of life enshrined in the Approved Documents or Building Regulations but also – and of rising importance for insurers – is the robustness of fire protection for the building as an asset.

For structural timber or any other MMC system for that matter, the complete assembly of parts and systems forming a multi-occupancy building must meet the performance requirements for fire, airtightness and acoustic performance as a whole. This must be done within the context of changing guidance like the impending changes to BS EN 9991, the forthcoming updates to Approved Documents B and L of the Building Regulations, updated Future Homes Standards and other guidance which is generally becoming more prescriptive.

The insurance industry has raised concerns about the protection of timber structures from fire and water ingress and the STA has done much to put the timber frame industry at the forefront of addressing these issues. However, it is worth reflecting that the principles of fire safety also apply to other MMC construction systems like those that use cold or hot rolled steel framing or those built as volumetric units. Architects are very reliant on the technical know-how and expertise of manufacturers who design and test their own systems or on fire engineering specialists who form part of the design team. Encouragingly the STA has pooled much of the test information from timber frame manufacturers into one place on their website to add to their own.

We cannot live without healthy forests and perhaps many of us cannot live without wood in our lives, whether that be a timber-framed house or everyday furniture. We must make sure that these homes are constructed to the very highest technical standards and as buildings that must also play a big part in the fight against climate change.

Andrew Carpenter, CEO of the Structural Timber Association, explains how the use of timber in building construction can be beneficial for occupants and their well-being.

On average, we spend around 90% of our time indoors and there is a growing appreciation that the buildings we inhabit can have a significant impact on both our mental and physical health. The design and construction of the building can affect this in a number of ways from physical factors such as indoor air quality, acoustics and lighting to the psychological influences of the layout and materials used. Studies have shown that concentration levels in offices, learning and development in educational establishments, and even patient outcomes in healthcare buildings are all affected by our surroundings.

The use of timber in construction is growing due to the sustainability of the material as the only truly renewable building resource. and expanding its use throughout the building can have a number of health and well-being benefits.

Firstly, timber has been shown to reduce stress. A study by the University of British Columbia and FPInnovations found that the presence of wood surfaces in a room lowered sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation. This is the system responsible for physiological stress responses and is also intrinsically linked to blood pressure, digestion and healing.

Timber within buildings has also been shown to improve physical and mental wellbeing in other ways. A study commissioned by Forest and Wood Products Australia surveyed 1,000 Australian workers and found a correlation between the presence of wood and higher overall satisfaction and lower absenteeism levels, as well as improved concentration and productivity among employees.

Furthermore, timber offers better acoustic performance than other hard surfaces used in building design. Its ability to absorb sound prevents echoes and noise transmission through the building, creating a quieter and more peaceful environment.

Finally, given the link between timber and sustainability, the use of timber can have a positive influence on peoples’ perception of the buildings they inhabit. For example, people can feel good about living in a home constructed of natural materials. In a study conducted by the BRE, 62% of respondents saw climate change as an issue they should be concerned about and 96% said that they had already made changes to be more sustainable. Additionally, 43% said they would prefer to buy or rent a home that had a sustainability certification. In fact, approximately 1 in 5 were prepared to pay more for such a property.

The buildings we live, work and learn in represent a significant part of our daily environment and as such have an important role in our health and well-being. In addition to its well-documented structural and environmental benefits, timber can also help to create healthier places for people.

As the Government works to ‘build back greener’, the Confederation of Timber Industries (CTI) in partnership with Waugh-Thistleton Architects have hosted the UK Construction Minister Lee Rowley, on a site visit to the Black and White building.

The Minister was taken for a tour of the exemplary fully engineered timber building, which is owned by The Office Group (TOG), the premium flexible workspace provider with a platform of more than 50 buildings across the UK and Germany and will be the tallest timber office structure in London when complete later this year.

Boasting a powerful sustainable agenda, the hybrid structure comprising beech Laminated Veneer Lumbar (LVL) frame with Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) has resulted in 37% less embodied carbon than an equivalent structure built using steel or concrete, demonstrating how a shift towards the use of biogenic materials in construction could help the industry to significantly reduce its impact on the environment.

Following its release of the Build Back Greener Strategy Document, the Government has signalled a clear intent to increase the use of sustainable materials, such as timber, within construction as it seeks to meet its Net Zero obligations.

Key to the success of this endeavour, is increasing the awareness and knowledge of structural timber. As such, the CTI is actively engaging with the Government and other stakeholders via the Timber in Construction working group, set up to develop a policy roadmap to help the Government deliver on its environmental ambitions.

Speaking on the visit is Andrew Carpenter, Director at the Confederation of Timber Industries: “Independent bodies such as the Climate Change Committee have already said that increasing the use of timber within construction is crucial to achieving net zero status by 2050, because of the low-carbon benefits of these forms of construction.

“The sustainable benefits of timber as a form of carbon capture and storage are widely known, and today has been about illustrating how these benefits are already being delivered safely across the UK, as well as globally, to create a new wave of low-carbon construction.

“In partnership with the UK Government via the Timber in Construction Working Group, and together with members of Parliament through our APPG for the Timber Industries, we are helping bring forwards the benefits of greater use of structural timber.”

Construction Minister Lee Rowley commented: “It was fantastic to visit the Black and White building to see how this innovative approach to building, harnessing engineered timber, is helping to drive sustainability in the construction sector.

“The site’s construction is an excellent example of the benefits timber buildings can bring and I look forward to seeing it when it is complete and in operation.”

Andrew Waugh, Founder and Director at Waugh Thistleton Architects, commented: “It’s great to see the Government taking an interest in engineered timber construction. We need Government leadership and systemic support for the use of regenerative, low carbon construction materials if we are to have any chance of reducing the impact of our industry on the planet.”

Charlie Green, co-Founder and co-CEO of TOG commented: “The Black and White Building is set to be Central London’s tallest mass timber office building. Alongside Waugh Thistleton, we have worked to reduce embodied carbon as much as possible, delivering a building that represents what future workspaces should be.

“It has never been more important to develop techniques and approaches that deliver buildings for a better world. Innovative construction processes and sustainable materials, like those employed here, will form a central part of the sector’s journey to net zero over the coming years.

“We’re really pleased that Lee Rowley, MP, visited the site today to see this evolution in practice and look forward to further engagement.”

For more information on the Confederation of Timber Industries, please visit: www.cti-timber.org.

For more information on the Waugh-Thistleton, please visit https://waughthistleton.com/

WHEN DOES TIMBER MAKE SENSE?

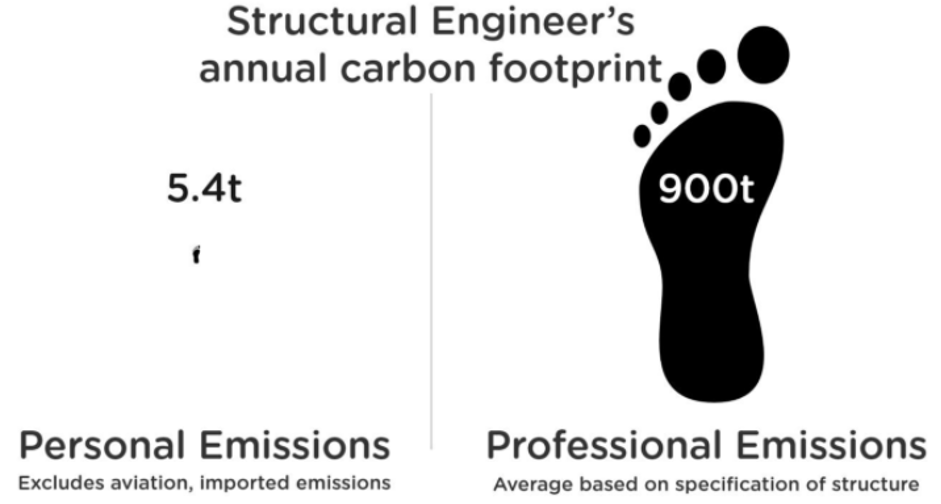

Individuals can make a limited difference to the climate challenge with their daily choices. Yes, we can all do lots of green things in our lives – we can choose not to fly, drive electric cars and eat less meat – this is of course important, but in most instances the reality is that reducing professional emissions will have the biggest impact on achieving a low-carbon society.

As a structural engineer, I am personally responsible for managing huge masses of carbon dioxide. With the strike of a pen, I could add hundreds of tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere – or make significant savings. That is why it is so crucial that those of us who specify buildings recognise the enormous importance of choosing lower-carbon solutions where possible.

Professional responsibility

Currently, the construction industry represents around 10% of total UK carbon emissions and directly contributes to a further 47%. As a result, the industry finds itself in a position of great accountability and influence with regards to the nation’s climate change efforts.

Those who design buildings and the structural engineers who determine the frame type have a huge responsibility within the construction industry. Typically, a UK structural engineer’s professional carbon footprint is around 160 times their personal carbon footprint for scope 1 and 2 emissions.

While the industry is taking steps to develop more sustainable working practices, there is a corresponding growth in demand for more sustainable development options from employers and investors and the industry needs to respond to that demand.

Enhanced public awareness of climate change, including a growing understanding of the economic risks it poses, has caused environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations to rise up corporate agendas. This has resulted in a shift in perception, where ESG is no longer considered a risk to be managed, but rather is a significant driver that is informing company strategy for long-term growth. Traditional barriers to the adoption of more sustainable development, including perceived higher costs and a general lack of awareness, are being outweighed by the increasing importance of ESG in investment and procurement decisions.

Carbon sequestration

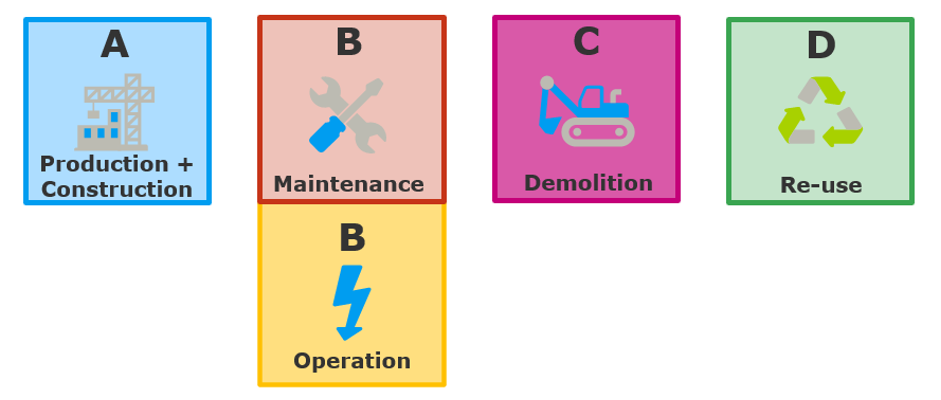

As we know, when trees grow they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere locking it away as carbon in the cells of the tree. The reporting of this carbon sequestration is often a source of debate with potential confusion and inconsistency. This often stems around when the carbon sequestration is considered. To help demystify this life cycle analysis can be used which breaks a product’s life cycle in stages. The standard used for this, BS EN 15978, can be broadly broken down into the following modules.

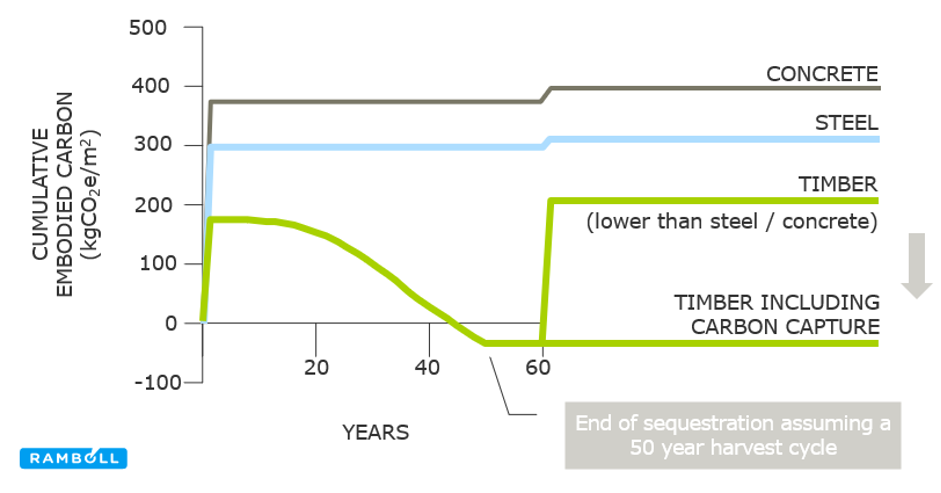

Module A dominates the life cycle emissions, particularly as we see decarbonisation in the operational aspects found in module B. Steel and concrete require a high-energy production process, but energy consumption for timber is also significant due to the harvesting, drying and sawing. Confusion with timber occurs as the amount of carbon stored within wood can be greater than the module A emissions and in some reporting is quoted as immediately carbon negative. This approach would mean that using timber excessively in a building is better for the environment – this is obviously not the case.

There are positives to sequestering atmospheric carbon within long-term timber projects as they act as a carbon sink which is beneficial to the climate. For example, over a 50-year harvest cycle in a managed forest a new tree(s), that has replaced the harvested tree, grows large and sequesters carbon from the atmosphere thereby achieving a carbon negative position. After 60 years of the building’s use, carbon is potentially released back into the atmosphere as the building is either sent to a landfill or burnt in a biomass boiler.

However, in 60 years, it could be appropriate to consider that carbon capture technologies will mean that no further carbon is emitted at the end of the life of the building. Consequently, the timber building remains carbon negative due to the carbon sink of the replacement tree(s) – steel or concrete cannot do this. It should also be noted that an efficient timber design, one which has reasonable grids and optimised design, typically has a lower embodied carbon than either steel or concrete buildings.

Accounting for sequestered carbon is a significantly debated subject, and there is much confusion and inconsistency surrounding it. Reporting sequestration alongside the reported figures of module A or a negative emission can generate the belief that using timber in excess is beneficial to the atmosphere. However when designed efficiently timber frames can be a much better option than steel or concrete frames.

At Ramboll we present our carbon figures in a clear and transparent manner so that clients can make informed decisions about the carbon impact of their projects.

At this point in time, timber currently can offer a lower carbon solution than either concrete or steel with timber having the opportunity to be carbon negative over a 50-year cycle.

If we specify and construct more timber buildings, this will buy us time against climate change to allow technologies to develop to an appropriate level until we can potentially utilise permanent carbon storage technologies or the expected lowering of embodied carbon of concrete and steel in the future.

Currently, timber is an incredibly effective and sustainable building material. However, it is equally important to understand that there isn’t an infinite supply, so attention must be paid to ethical forestry and timber sourcing to safeguard the future of timber as a material.

We currently have the understanding and tools to rationalise our design decisions with respect to the embodied carbon and, for now, timber buildings certainly form part of the solution in addressing the climate crisis.

For more information please visit www.ramboll.com

Here Andrew Carpenter, Chief Executive of the Structural Timber Association, looks at where the timber construction sector currently stands and where it could go next.

The use of timber in construction has received increased attention in recent months and years. As the issue of sustainability and climate change has become more acute, we are seeing many architects, contractors, housebuilders and clients looking at how the use of low carbon materials can be expanded. Timber has been at the forefront because it is a versatile material that has a long history of use in construction.

In fact, feedback from our members shows a marked trend towards the use of timber frame, with private developers in particular investing heavily in timber-based offsite construction. Several key housebuilders have acquired businesses in their own supply chain to secure manufacturing capabilities. For example, in 2018 Countryside acquired the Westframe timber frame manufacturing facility and Barratt Homes purchased Oregon Timber Frame the following year. In Scotland, Miller Homes acquired Walker Timber at Bo’ness to expand its business. Persimmon Homes also has its own timber frame manufacturing arm, Space4.

We are also seeing an increase in demand for timber solutions within the affordable and social homes market. For example, L&Q Homes has formed a strategic partnership with Stuart Milne Timber Systems to increase its delivery of timber frame homes. Furthermore, the Welsh Government’s Innovative Housing Programme, launched in 2017, provides funding to support low carbon affordable housing. The most recent round of investment saw £35 million pledged to deliver 400 factory built homes, with many being built using timber frame.

While some parts of the world, including Scotland, already have a long-established and very successful heritage of building in timber frame, England is still very much reliant on masonry. Therefore, for timber systems to become used more widely, the first hurdle will be overcoming the culture within housebuilding that focuses on ‘traditional methods’ as well as the hesitancy around alternative methods.

A big part of this will be raising awareness about the benefits of timber, particularly with regard to its ability to contribute to Net Zero Carbon, which is becoming increasingly urgent. While traditional building methods are aiming to be carbon neutral by 2050, timber offers the opportunity to achieve net zero now. What’s more, with the use of timber now enshrined in the Government’s Build Back Greener strategy, more widespread adoption of structural timber seems inevitable.

Embodied carbon emissions account for up to 75% of a building’s total emissions over its lifespan. This can be reduced significantly using the right low carbon materials, and timber products have the lowest embodied carbon of any mainstream building material. In fact, every cubic metre of timber used in construction has absorbed 1 tonne of carbon dioxide, which will be stored for the lifetime of the product. Increasing the use of timber in construction, is the quickest and most effective way for the UK to deliver on its economic, employment, housing and climate targets without delay.

In addition to housebuilding, one of the biggest potential growth areas is the public sector. Engineered timber solutions such as CLT (Cross Laminated Timber) have huge application potential for public buildings. In 2019, the Government announced the Health Infrastructure Plan, which includes a commitment to building 40 new hospitals by 2030 and a focus on Net Zero, digitalisation and Modern Methods of Construction. Under the plan, schemes must include 70% offsite construction, which leans heavily towards timber as the primary building material, in order to secure funding.

We are also seeing timber increasingly used as a solution to limitations on space and the pressure on brownfield sites in urban areas. Many developers are looking to maximise residential capacity by adding extra storeys onto existing buildings, particularly in heavily populated areas. Thanks to its lower weight and high strength, engineered timber is an ideal material for achieving this without needing to make significant reinforcements to the building’s foundations.

Offsite manufactured engineered timber also has further advantages for reducing the impact on the local environment. One of the key benefits of offsite construction is reducing the number of vehicles going to a site. The use of timber enhances this further as the lower weight compared with other materials allows more to be safely transported on each vehicle. Lowering the overall weight of the building also means smaller foundations and less excavated material that needs to be removed.

With so much potential and a wide range of opportunities to expand the use of timber, the coming years will be an exciting time in the sector. However, it is important for the Government to continue to support the use of timber, modern methods of construction and the development of low carbon innovations.

At the STA we are actively working to promote the benefits of timber to the wider industry, overcome the barriers to its widespread adoption and are committed to helping our members take advantage of the push for low carbon construction.

For more information about using structural timber or working with an STA member, please visit: www.structuraltimber.co.uk

Local authorities throughout the UK are facing great difficulty as they attempt to rapidly increase their housing stock and deliver affordable homes, whilst also meeting environmental targets. Here, Andrew Carpenter, Chief Executive of the STA, discusses how timber frame construction provides the perfect solution, offering a sustainable, low-carbon method that can be delivered at pace.

The Climate Change Act 2008 committed the UK to reducing its carbon emissions by 80%, relative to levels recorded in 1990. In 2019, following advice provided by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), the Government increased its target to a 100% reduction by 2050, or ‘Net Zero by 2050’. Whilst this ambition to improve the UK’s environmental impact is a welcome one, many are finding this target difficult to meet. At the time of writing, 74% of councils in the UK have declared a climate emergency. There is no single definition for what constitutes a ‘climate emergency’, most are proclaimed at a point in which a council believes it is no longer on track to meet Government climate targets, such as Net Zero by 2050. One issue that councils are particularly struggling to overcome due to environmental targets, is meeting the growing demand for housing.

The UK’s housing crisis is nothing new, in 2015 the Government set out an aim to build 300,000 homes a year to combat this. However, this target has not been met and recent estimations suggest that 345,000 new homes are now required to be built each year to overcome the backlog. The crisis is exacerbated further by the ever-increasing need for affordable housing. In the 2017 UK Housing Review Briefing Paper, the issue of affordability was described as “neglected” for both private and social housing. Today, local authorities are finding it difficult to balance producing homes at an affordable rate whilst also meeting environmental targets.

Many had hoped the Government’s Future Homes Standard document, would offer some guidance to house builders and local authorities on how best to overcome the numerous obstacles they have to navigate. Whilst some valid recommendations were made, structural timber and the wealth of environmental benefits it possesses were entirely overlooked. We believe that timber frame technology in particular can provide the solution to the sustainability, cost and demand issues facing local authorities.

Environmentally, the advantages of building with structural timber are vast. Firstly, when compared to its competitors, timber is the stand-out performer, possessing the lowest embodied carbon for any building material. Secondly, as long as forests are properly managed and maintained, timber provides us with the only truly renewable building resource. Thirdly, as they grow, trees sequester and store carbon from the atmosphere – meaning that throughout its lifecycle, timber has a carbon negative impact. Lastly, timber offers exceptional energy efficiency performance, greatly reducing household emissions – a positive for both the environment and the pocket of the homeowner. Aside from its environmentally beneficial properties, prefabricated timber frame technology could prove to be a great assistance to meeting the demand for affordable housing.

On average, using timber frame systems can reduce the construction time by eight weeks, when compared to traditional masonry methods. This is largely because timber frame is manufactured offsite and delivered as prefabricated panels that can be erected within days. Additionally, producing timber frame systems offsite massively improves reliability. Firstly, as they are produced in controlled factory environments, quality control is assured, resulting in fewer errors during assembly. Secondly, the fabrication of timber frame systems in a factory is not weather dependant, meaning build programmes become far more predictable. This speed of construction and greater reliability help to keep project costs low. With less labour required and fewer issues regarding quality, timber frame systems provide local authorities with the means to build more homes, at a lower cost.

Local councils are fighting a hard battle as they attempt to balance the demand for affordable homes while also meeting environmental targets. If they are to succeed, any attempts to solve this issue must include more widespread adoption of timber frame systems.

To find out more about timber frame, visit our website: https://www.structuraltimber.co.uk/timber-systems/timber-frame

It’s not just the UK that stands to benefit from the wider adoption of structural timber building solutions. In fact, there are a number of countries which could also use the material to meet crucial development targets and reduce levels of carbon consumption.

That’s why we recently launched our ‘Timber Around The World’ series of blogs. This month, we talk to Tim Buhler, Technical Manager at Wood WORKS!, a market development initiative in Canada.

Hi Tim – can you explain what Wood WORKS! is?

It’s been launched by the Canadian Wood Council Programme and the organisation’s main aim is to help to grow the use of wood products in construction. In that sense, it’s really similar to the ‘Time for Timber’ campaign in the UK. We act as the Canadian voice for the wood products industry and help to educate design professionals on where and when to use the material.

In practice, we act in the same way as a standard national federation and incorporate all aspects of timber products; from structural two by fours, all the way up to mass timber CLT manufacturing. We want to make sure that developers feel confident in specifying wood products and to ensure they have the right support. With our assistance, we’re confident that we can help to grow the market across the country.

Personally, I work on the market development side of operations. So, my main goal is to get the word out about the benefits of wood products. There’s another team at the Canadian Wood Council that focuses on engineering and building codes, as well as making regulations more accepting towards the use of wood products. Collectively, we work together to make sure we’re reaching all relevant parties.

What’s the biggest obstacle to using timber in Canada?

As a nation, we don’t tend to build homes from materials like concrete, or brick. Therefore, we’re in a rather unique situation where the vast majority of residential construction (up-to three storeys) is already built from timber. However – it’s very rare for buildings larger than that to be constructed from timber. There’s a number of reasons for this, but one is a lack of education about the material’s suitability to this form of construction.

Over the years, we’ve worked hard to tackle this education issue, but there’s still more to be done. Currently, the number of courses in colleges and universities that relate to steel and concrete construction vastly outnumber those relating to timber. With that said, there is nothing specific in our building codes to prevent more timber construction. As a result, the task is about changing mindsets.

Can environmental goals help to encourage that change?

Absolutely. Like so many other countries, Canada faces a challenge of dealing with growing population levels, whilst also trying to limit carbon consumption. We believe wood can have a major impact in this area. As a nation, we’re still going to need to build more homes, but sustainably. Thanks to wood construction, you have that option and can effectively tackle both goals.

We’re already seeing the appetite growing across parts of the country. For example, the market in British Columbia is already really strong. At the same time, there’s new timber developments popping up in throughout Canada, which are gaining positive attention.

How can the Canadian Government help in this effort?

The government is already assisting in these efforts. Federal and provincial governments are major supporters of our programs. In addition to the local benefits, as a major exporter of wood products, Canada’s economy stands to massively benefit from the wider adoption of materials like structural timber. That’s another big reason to support the industry. So, even if you’re a politician who doesn’t put too much emphasis on improving environmental performance there’s still a strong economic argument to back developing the sector.

Is the insurance sector an issue that you need to overcome?

Yes, it’s certainly a roadblock. The good news is that as more large timber buildings are built there’s more historical data for insurers to compare when putting together their rates. The bad news is that we’re still working through that process and there remains obstacles we’re yet to overcome.

Ultimately, if people are financially disincentivized to use timber then that will have an impact. With the high insurance rates on certain forms of building types that’s sadly what’s happening now. Even builders who are very committed to the material aren’t going to use it over making a profit. Our job is to level that playing field.

What does success look like in the next ten years?

We’re working towards a number of aims. From the insurance side, we want to help develop a better understanding of timber as a material and to assuage some of the unfounded concerns about its performance. We’re hoping to see projects receive more favourable building classifications. For example, it would be a huge step forward to see some mass timber buildings recognised for their increased fire resistance and moved out of the insurance category they currently share with light wood frame buildings.

We’re also looking for more communication with the industry. Our model has been successful in the past, so now it’s about rolling that out and reaching more architects and engineers. Likewise, we want to ensure we’re speaking with developers and owners about the material’s benefits. By working on a building-by-building basis, we hope to be able to inspire more wide scale adoption.

Whilst ambitious, we think these goals are realistic, especially in light of the need for the building sector to adopt more sustainable practices into its operations. In the next few months, we’re going to see 12-storey mass timber structures receive the green light in our National Building Code, which is really positive.

Finally, I’d love to see more global collaboration from like-minded organisations representing the timber and wood construction industry. We’ve had preliminary meetings with similar bodies in Austria, Australia and China, as well as the work we’re already doing with the Structural Timber Association. There’s so much potential for us to come together and amplify our voice on a global level.

To find out more about the work that Tim does as part of Wood WORKS! and the Canadian Wood Council, please visit: www.wood-works.ca