“He’s a builder, he’ll just know how to build it.” This was the response Tabitha Binding, Head of Education and Engagement at Timber Development UK, received when supporting a winning group of student architects to make their successful timber-framed concept an installation reality at the London Design Festival.

Yet when Tabitha sat down with the architects and expert carpenter enlisted to build the installation, they found they were all talking a completely different language.

The architects were communicating with 3D software, while the carpenter, using pencil and paper, was seeking to understand how the dimensions met to ensure the structure would be supported correctly. Through collaboration, help from other timber trade experts and hands-on experience during the installation’s construction, all parties shared their knowledge and the communication barriers disappeared.

Encouraging education and engagement around the use of timber in construction, as Tabitha’s job title suggests, is exactly what her role is all about. During this interview, we discover why we need to educate and upskill the students of today, who will become tomorrow’s specifiers, designers, engineers, project managers, quantity surveyors and contractors. We need everyone to understand how to use timber wisely if we are going to create a future full of low-carbon timber construction.

What is your role and why is it important for timber construction?

I work with industry, professionals, academia, and students to enthuse, encourage and educate – to increase knowledge and competency in timber as we transition to a biobased economy.

With 5,000 architecture and 5,000 engineering students entering the world of construction and the built environment every year, business as usual is no longer an option. We have to change the way we build to create a low carbon, sustainable future.

We spend our lifetime in buildings and most of our money on our homes. And yet, while architecture and engineering are viewed as ‘suitable’ career choices, construction itself often isn’t, despite its vital importance to the UK economy. Let’s face it, without construction experts to build our homes and buildings, we’d be pretty stuck.

The most impactful decisions on carbon emissions in the built environment are made long before the foundations of a building are laid down. They happen in architects’ studios, within the offices of city planners, and in the engineering space. Decisions made during the project development phases impact both operational and embodied emissions, as well as how residents will live and work in these structures.

My role is to bring the design and delivery disciplines together to build better and understand more clearly the purpose of each building, to give everyone pride in their work and stimulate mutual respect across the timber construction supply chain.

What are the main roadblocks to creating low-carbon buildings in the UK?

One of the key roadblocks has been the educational gap around timber, which often features as little more than a day of learning and coursework within some universities. Departments can be disparate with scant collaboration across the built environment subjects, and some less progressive universities are even still teaching outdated methodologies. As a result, many students simply don’t know any better. Many also don’t have any hands-on experience that can contribute to a more rounded and knowledgeable approach to timber construction.

This means graduates emerge without the knowledge, ability, or confidence to employ timber systems. With our University Engagement Programme, we are seeking to change this – and make timber systems and technologies a core pillar of any built environment course in the UK.

What other initiatives are you implementing to overcome the timber-related education gap?

An important part of what I do is delivering project-based learning that breaks down barriers between professions, and facilitates dynamic learning and practical, transferable timber skills.

One way we do this is by running interdisciplinary challenges where Timber Development UK (TDUK), the now amalgamated Timber Trade Federation (TTF) and Timber Research and Development Association (TRADA), hosts a workshop based on a real-life project.

For example, the one we did just before lockdown was sponsored by timber industry partners and saw 58 students from universities across the UK gather at Cardiff University and compete to design, cost and engineer the best low-carbon, energy and water efficient timber community housing in less than 48 hours.

Each team consisted of student engineers, architects, architectural technologists, quantity surveyors and landscape architects, and received hands-on support from pioneering design professionals and industry members, including judges from Mikhail Riches, Cullinan Studio, Stride Treglown, Ramboll, BuroHappold, Entuitive, Gardiner & Theobald and PLAN:design.

How is the STA supporting your quest?

Last year’s competition Riverside Sunderland University Design Challenge (RSUDC21), saw 300 students design, engineer, plan and cost a three-bed family home along with an indicative masterplan for 100 homes to meet RIBA2030 Climate Challenge targets – with low-carbon timber and timber-hybrid systems providing the main material focus.

The STA’s chief executive, Andrew Carpenter, spoke directly to the students during the weekly Friday ‘virtual catch up’ session and enabled access to the STA’s vast information library whilst the Association’s Technical Consultant also supported the event, delivering a webinar on timber and fire. They were among 78 professionals who participated across a 12-part webinar series, which proved to be a unique and ambitious learning opportunity for the whole industry. Experts presented on everything from sustainable timber and offsite manufacturing, counting carbon, timber challenges and structural engineering to how you cost and budget timber to post-occupancy evaluation – the webinar series is still available as a learning asset on YouTube.

Are there any specific hotspots in the timber supply chain that you’re focusing on going forward?

Yes, definitely. One hotspot is the point at which design and construction meet. Tackling this collision proactively, I’m currently working strategically with New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering (NMITE) as its Centre for Advanced Timber Technology (CATT) Lead for External Engagements and Partnerships to deliver training that encourages greater design and construction collaboration across the supply chain.

We’re looking to develop some short courses and CPDs into a longer Bachelors degree in Sustainable Built Environment over the next year and, starting in September 2022, we will be running some interactive education days that will bring together the whole supply chain.

These will invite architects, engineers, clients and cost consultants, contractors and timber industry supply chain experts, such as offsite frame manufacturers, to up skill, reskill and address topical industry issues. Topics on the table embrace everything from level foundations to air tightness and energy performance and, of course, tackling the reduction in carbon at element, building and operational levels. Allowing people to exchange really good knowledge and encourage more collaboration will ensure that where we build with timber, we also build better with timber.

How did you find yourself in the timber industry?

I started out aged 17 working with coppiced hazel and softwood thinning. My first engagement with the timber construction industry was when I joined the Welsh timber charity Coed Cymru Cyf in 2010. The charity focuses on creating and managing Welsh woodlands for multiple benefits.

From there I was involved with ‘Tŷ Unnos’ – literally translated as ‘a house in one night’. The name was chosen to convey a fast and adaptable building system making use of local material and local labour, all based around Welsh timber. It led to the development of a fully certified volumetric offsite system, where buildings left the factory fully finished and fitted. That’s when I got involved with post occupancy evaluation, design for manufacture and assembly, plus disassembly & reuse and the Passivhaus energy efficiency standard.

I’ve also worked on European technical guidance, thermal modification of Larch for joinery with Bangor University, a Wood Encouragement Policy with Wood Knowledge Wales, which was adopted by Powys County Council in 2017 and, more recently, joined TRADA in 2018 to focus on education and engagement in universities. The rest, as they say, is history!

Do you have a takeaway message for the industry?

Absolutely. It’s all about collaboration early on. If we work together across disciplines we will have more fun, be more productive, less wasteful and create better buildings that are both energy and resource efficient and beneficial to human and planetary health.

To join in, keep an eye on the new Timber Development UK website for the collaborative opportunities arising when we launch in September. https://timberdevelopment.uk

Connect with Tabitha Binding on LinkedIn

The STA echoes this collaborative approach, working closely with members, stakeholders and the UK construction industry to address the issues that timber construction faces. The STA’s mission is to enhance quality and drive product innovation through technical guidance and research, underpinned by a members’ quality standard assessment – the STA Assure Membership and Quality Standards Scheme.

For more information visit: https://ttf.co.uk/

Stewart Dalgarno is the Director of Innovation and Sustainability at the Stewart Milne Group, one of the UK’s largest independent award-winning housebuilders. Here is his thinking as to why now is the time for timber.

How do you develop your expertise in timber construction?

I developed my expertise in timber construction through working with the Stewart Milne Group for the last 38 years, as a house builder and as a timber frame manufacture. During that whole career I have lived and breathed timber frame construction, at the core of what we do, as a residential house builder.

What are you such an advocate for the use of timber in construction?

I am an advocate for the use of timber in construction because I just think it is the right thing to do from a sustainability point, but commercially, from a profit point of view, it is the most valuable commercial, attractive, simplest way to build homes. For the last 30 years we’ve been using timber construction and we would not be in the place we are today without using timber.

How has the industry changed in the time that you have been involved?

I have seen lots of changes in the industry since I’ve been involved, with the growth in the marketplace for timber frame construction in Scotland – 85% is timber framed. This is my heritage. I’m glad to see in England it has also increased now and will continue to grow. We’ve seen challenges come our way, but we have improved solutions that give us confidence going forward, to see the challenges in net zero carbon. On many occasions we’ve developed net zero carbon homes that will be, I think, something we will be proud of going forward in the future of the industry.

What are the benefits of modern methods of construction (MMC)?

The benefits of MMC are clear in my mind. As a housebuilder we see speed, quality, surety – a build on time – as being critical. Also, we are less reliant on bricklaying and critical skills are short in the marketplace. Using timber frame construction, for us, solves all of that.

Why is timber frame NOT the preferred method for many housebuilders?

The barriers to the uptake of timber construction I think of are just knowledge and sharing of good and bad experiences and learning from that – overcoming some of the perceptions that will arrive in the marketplace. For 45 years we’ve been building timber frame homes. We can get insurance. We can get warranty. We can get mortgages. We have never had a problem in our history of building timber frame homes.

What more needs to be done to increase the use of timber?

There’s more we can do to educate people on timber construction. There are lots of new forms of timber related construction in the market, such CLT (cross laminated timber) mass timber construction. So, more tests…more education…more knowledge centres. More innovation brings confidence in the marketplace, taking people with us on the journey – key people like warranty providers, lenders and insurers. To me that is one of the key things we should be doing more of to encourage more timber being used in the sector.

Can you summarise the benefits of timber for us?

The benefits of using timber compared to other materials for house builders is really the speed, quality, but really the sustainability credentials. We are finding through our ESG requirements nowadays that it is quite important to demonstrate, by using low embodied carbon materials. The fact that we use timber gives us a tick in that box, substantially, straight away.

What is the wider market for the use of timber in the housebuilding sector?

The wider market for timber frame is exciting and it’s progressing quite a lot. We see a lot of new housebuilders coming into the marketplace, small SME type developers, private rental developers, affordable developers and they’re all looking to use smart ways of building homes and really timber frame here is the ‘here and now’ answer for them.

How does timber frame meet the needs of the Government’s ‘Build Back Greener’ strategy?

Timber frame construction meets the build back better, build back green agenda because of its sustainability credentials. The fact there are less skills needed on a timber frame housing site than a traditional site and it’s just viable, so we can all enjoy the economic benefits of building new homes here in the UK.

How have you found your dealings with the insurance industry and what does it need to understand?

We have worked with them for many, many years and we ensure we have got the right standards, right qualities, the right fire tests of the kits and everything you need to technically prove this is a ‘here and now’ proven solution.

How does timber fit with the Future Homes Standard?

Timber fits with the Future Homes Standard very well. One of the key criteria of that is an energy efficient fabric. We have always believed in a fabric first approach, fit and forget, where you have got the insulation within the timber frame wall system and therefore you are reducing the heat load. That allows other technologies like solar panels and heat pumps that then decarbonize your home, to make the Future Homes Standard, to get to a net zero carbon outcome.

What do you think is the future for timber frame construction?

The future for timber frame construction, for me, is to do more in the factory and less on site. We’ve got a good heritage of making things, we can do more in the factory through automation – to put in insulation, put in windows, then maybe cladding, then maybe services. We’re bring a whole house system, a panelised system. We firmly believe it is the way to go. We think timber frame can be at the heart of that future.

Andrew Waugh, Founder and Director at Waugh Thistleton Architects, was part of a recent visit by Construction Minister Lee Rowley MP’s to The Black & White Building. Designed by Waugh Thistleton and owned by The Office Group (TOG), the fully engineered timber building providing premium flexible working space, will be the tallest timber office structure in London. Andrew discusses why the visit was so crucial to the Confederation of Timber Industries (CTI), which is an umbrella organisation representing the UK’s timber supply chain, and with which Waugh Thistleton is in partnership.

Government legislation that promotes the use of timber throughout the construction industry is required in order for the UK to meet its net-zero commitments. However, due to the number of interwoven alliances and systems within the legislation, it’s simply not as easy as taking building materials out and replacing them with another, which poses a big problem. There are also more speculative parts of the industry that present challenges, such as the nervousness and concern surrounding insurance and pricing.

The minister’s visit to The Black & White Building was crucial because it was proof of concept. We were able to demonstrate that timber constructions are cost equivalent to a concrete building, faster to construct, ensure better working conditions on-site and produce a building with a higher financial value. Additionally, landfill waste is minimised and there’s an 80% reduction in site deliveries, which all contribute to more sustainable construction practices. We were able to show the minster what a low carbon construction can look like.

A lot of work around sustainability over the past 20 years has been centred on layering additional systems such as triple glazing, the addition of more insulation, building management systems and mechanical heat recovery, but what we really should be focusing on is making things simpler. Timber buildings allow us to find the beauty in simplicity, and to design sufficiently for the purpose of the building and not beyond, which is something that the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report explores in more detail along with a global assessment of climate change mitigation progress, along with potential approaches to the overall issue.

It is a fact that timber is currently the only viable alternative to steel and concrete, additionally, it is an existing technology with a sophisticated supply chain. We must reduce our reliance on steel and concrete, ideally by reducing the use of both materials by 50% in the next 8 years, and replacing them with timber. As timber is a uniquely replenishable structural building material for high-density urban construction, we have the opportunity to demonstrate a clear alternative way of doing things, by using an existing system to prompt the evolution of construction.

These changes must happen immediately, and in terms of demand and availability, timber is incredibly well-suited to adopt this in a short time span. In Europe, more than half of the trees felled are burned, so we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of the opportunities with timber, and the timber manufacturing industry is growing exponentially. Governments in Europe and North America are changing their changing building codes and adapting legislation to promote the use of structural timber; the UK is unique only in its failure to do so with the same haste.

It was incredibly important for the minister to visit The Black & White Building to get a good look at what the other countries are getting so excited about, which is a technology that was innovated in the UK and exported around the world by UK firms. The time is upon us to catch up and for the UK Government to take the same action that many others have already taken.

To learn more about The Black & White Building, and other Waugh Thistleton sustainable projects, visit: https://waughthistleton.com/practice/

To read about the Construction Minister’s visit to The Black & White Building, visit: https://www.structuraltimber.co.uk/news/structural-timber-news/uk-construction-minister-visits-ground-breaking-low-carbon-timber-building-in-london/

Using the generic term ‘wood’ is analogous to using the word ‘food’. Wood covers an estimated global diversity of over 20,000 woody species of plant. A few thousand of these are commercially used and these are as diverse as the cultures that use them. Wherever we look, the use of wood is deeply rooted in human history and indeed in everything we do today.

When I think of ‘wood’ I think of an ingredient that can be transformed from a renewable material resource into a gourmet feast of colour, texture, and pattern or used simply as a mass-produced component that we order from the builders’ merchant. The designs we dream up sometimes rely on individual trees where we want something special, but we are most likely to rely on standard sawn or Planed All Round Timber (PAR) sizes harvested and converted from forest trees and readily connectable using metal fixings like a Meccano set. Whichever way we use wood we must only specify sustainably sourced timber from schemes such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) to help protect them as a regenerative resource. Thankfully most timber suppliers now endorse these schemes and provide a range of timber products with trusted certification.

There is no other material like wood and it is so easy to use once you have familiarized yourself with its properties and available sizes, which do vary considerably from softwood to hardwood and across the available species. As an architect, this is what makes designing, specifying, making joinery and furniture and especially working with those skilled in the art of woodwork in all its forms, so rewarding.

The versatility of the material is as diverse as its applications. The relative lightness of this material is balanced by its strength and for some species, the ratio of these is better than steel. When exposed as a finish there are exquisite tactile qualities to choose from as well as a softness in light which is so appealing in exposed CLT construction. There are now multi-occupancy buildings where CLT has been used as a wall or ceiling finish – even the stairs and furniture can be made from this material. These advantages of using the wood stem from the connections to the forest that is then recreated itself in the home.

Cutting edge zero-carbon houses need to incorporate as much wood as possible to sequester carbon. This is important as it is the most practical way to reduce or even produce a negative carbon footprint. But the mindset for sustainable thinking starts with choosing the right materials. Foundations can be minimised using light timber framing and by making the most of the engineered timber products available which now play a significant role in MMC. I also see more interest in systems that are hybrid in nature and incorporate steel connections and consider thermal mass to assist with mitigating overheating now that the new Approved Document O must be met. Meeting the overall building physics strategy is essential to futureproof the asset so that it is insurable, mortgageable and comfortable to live in.

Moving up the scale, multi-occupancy mid-rise apartments can be constructed in timber frames or CLT but architects and engineers must understand the material and its possibilities and limitations. A decade ago, when low U-values became central to developers’ sustainability ambitions and Approved Document L of the Building Regulations cranked up demands for lower U-values, the Structural Timber Association (STA) began to develop new high performance-tested wall, floor and roof types to address this. These now form pattern books available for download on their website.

Architects’ demands on timber frame-based building systems must now change to align with the requirements of the Building Safety Bill. Design teams are now expected to demonstrate that they have the relevant experience and expertise to design buildings and are expected to use comprehensively tested systems and to pass Gateway 2. No home should be built unless it is constructed safely and competently and, of course, can be maintained as such thereafter. This is foremost for the protection of life enshrined in the Approved Documents or Building Regulations but also – and of rising importance for insurers – is the robustness of fire protection for the building as an asset.

For structural timber or any other MMC system for that matter, the complete assembly of parts and systems forming a multi-occupancy building must meet the performance requirements for fire, airtightness and acoustic performance as a whole. This must be done within the context of changing guidance like the impending changes to BS EN 9991, the forthcoming updates to Approved Documents B and L of the Building Regulations, updated Future Homes Standards and other guidance which is generally becoming more prescriptive.

The insurance industry has raised concerns about the protection of timber structures from fire and water ingress and the STA has done much to put the timber frame industry at the forefront of addressing these issues. However, it is worth reflecting that the principles of fire safety also apply to other MMC construction systems like those that use cold or hot rolled steel framing or those built as volumetric units. Architects are very reliant on the technical know-how and expertise of manufacturers who design and test their own systems or on fire engineering specialists who form part of the design team. Encouragingly the STA has pooled much of the test information from timber frame manufacturers into one place on their website to add to their own.

We cannot live without healthy forests and perhaps many of us cannot live without wood in our lives, whether that be a timber-framed house or everyday furniture. We must make sure that these homes are constructed to the very highest technical standards and as buildings that must also play a big part in the fight against climate change.

The Structural Timber Association has been invited to participate in the Timber in Construction Working Group which brought together key industry stakeholders to develop a policy roadmap to help the Government safely increase the use of timber in construction, a crucial step in achieving the UK’s Net Zero target for 2050.

The Timber in Construction (TiC) working group is tasked with identifying significant actions that should be taken by the Government, the construction industry and the timber industry in order to increase the number of timber and hybrid structures built in the UK. To identify the key actions to take, a full understanding of the barriers faced in the construction industry is crucial. During a recent luncheon, the STA asked Mark Wakeford, Managing Director at Stepnell, what barriers he believes are preventing more widespread use of structural timber:

“Many of the contractors I represent struggle to use structural timber systems, as it costs them far more to insure than ‘traditional’ methods. There are, of course, some insurers that will back timber projects. If you can get the right information to the right people in the right insurance roles, we can expect a greater structural timber uptake. Bridging the knowledge gap between the timber and insurance sectors will be key.

“Aside from that, I think that solving the skills shortage will be crucial. Although the skills shortage is being felt across all materials, it is much easier to find a bricklayer than a CLT installer, for example. As such, this issue needs to be tackled sooner rather than later to see some success.”

The TiC working group has two primary objectives – to foster collaboration between sectors to develop a clear policy to increase timber in construction and to produce a policy roadmap to outline a clear implementation plan. Oliver Schofield, Co-Founder of Lignum Risk Partners, offered an interesting solution to increasing the use of structural timber in the UK and improving the accountability for material usage:

“We need to have a standardised system in place that provides insurers with access to much more robust data. Don’t be mistaken, many insurers would like to support timber projects but without the data or knowledge, it is difficult for them to do so.

“I think that the most effective solution would be to introduce a blockchain that can be used as a record. Everybody should be obliged by regulation to record their use of materials, whether sustainable or not. This will not only ensure that no corners are being cut, but it will also equip insurers with a wealth of data that is desperately needed.”

Many figures within the timber construction industry believe that boosting market confidence with lenders, insurance companies and warranty providers is the best route forward for a wider uptake in timber construction. Mike Ormesher, Director of the Offsite Homes Alliance, feels that more must be done to aid the education and understanding of timber and hybrid construction to alleviate any safety concerns:

“There must be an open channel of communication to help insurers and investors understand timber construction and allow facts to dispel the misconceptions of structural timber. Perhaps the use of workshops, seminars, webinars and physical roadshow demonstrations is the best route forward to improve this knowledge base of using structural timber in construction.”

Suzannah Nichol Chief Executive of Build UK voiced concerns over whether the construction sector is approaching challenges with those outside the industry in the correct manner:

“Within the construction sector, we spend a lot of time discussing issues that are not directly within our control, instead of addressing those we can influence head on. I believe that the issues with insurers and financers are exacerbated by the poor level of communication between the industries. To deal with this, we need to be speaking in a language that those outside the industry understand. Instead of shouting loudly about all the problems in construction, we should be speaking in simpler terms about what ‘good’ looks like in the industry in terms of build quality, materials, and competence, explaining what we are doing about each of these and what we need others to do.

To this day, certain terminology used within cross-industry discussions and documents confuse even those within construction, which will only add layer upon layer of confusion to those outside of it. We need to be clear about standards and competence, while communicating in layman’s terms to improve clarity across the board.”

While the policy roadmap produced by the Timber in Construction working group will not be Government policy, it will be submitted to ministers for approval. The Climate Change Committee (CCC) advises that increased use of timber in construction is required to achieve net-zero, suggesting that timber-frame new build houses need to increase from 28% to 40% by 2050 to achieve these carbon-neutral goals. This may sound like we have a great deal of time, but in reality, these changes must be implemented immediately to allow ample time for the environmental effect to be felt.

The STA works closely with industry stakeholders to address all the issues that timber construction faces in the industry, including those regarding insurance. The association continues to commission and compile a significant amount of research resulting in guides and whitepapers that provide a better understanding of the use of timber in construction from a risk management perspective. This research gives factual scientific data and statistical evidence to present to the insurance sector. The STA will continue to raise the profile of timber as a safe construction material, backed by scientific data and will support the TiC with this evidence along with its in-depth knowledge of the structural timber industry.

To find out more about the STA and to view research documentation and reports, visit: https://www.structuraltimber.co.uk/

As the Government works to ‘build back greener’, the Confederation of Timber Industries (CTI) in partnership with Waugh-Thistleton Architects have hosted the UK Construction Minister Lee Rowley, on a site visit to the Black and White building.

The Minister was taken for a tour of the exemplary fully engineered timber building, which is owned by The Office Group (TOG), the premium flexible workspace provider with a platform of more than 50 buildings across the UK and Germany and will be the tallest timber office structure in London when complete later this year.

Boasting a powerful sustainable agenda, the hybrid structure comprising beech Laminated Veneer Lumbar (LVL) frame with Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) has resulted in 37% less embodied carbon than an equivalent structure built using steel or concrete, demonstrating how a shift towards the use of biogenic materials in construction could help the industry to significantly reduce its impact on the environment.

Following its release of the Build Back Greener Strategy Document, the Government has signalled a clear intent to increase the use of sustainable materials, such as timber, within construction as it seeks to meet its Net Zero obligations.

Key to the success of this endeavour, is increasing the awareness and knowledge of structural timber. As such, the CTI is actively engaging with the Government and other stakeholders via the Timber in Construction working group, set up to develop a policy roadmap to help the Government deliver on its environmental ambitions.

Speaking on the visit is Andrew Carpenter, Director at the Confederation of Timber Industries: “Independent bodies such as the Climate Change Committee have already said that increasing the use of timber within construction is crucial to achieving net zero status by 2050, because of the low-carbon benefits of these forms of construction.

“The sustainable benefits of timber as a form of carbon capture and storage are widely known, and today has been about illustrating how these benefits are already being delivered safely across the UK, as well as globally, to create a new wave of low-carbon construction.

“In partnership with the UK Government via the Timber in Construction Working Group, and together with members of Parliament through our APPG for the Timber Industries, we are helping bring forwards the benefits of greater use of structural timber.”

Construction Minister Lee Rowley commented: “It was fantastic to visit the Black and White building to see how this innovative approach to building, harnessing engineered timber, is helping to drive sustainability in the construction sector.

“The site’s construction is an excellent example of the benefits timber buildings can bring and I look forward to seeing it when it is complete and in operation.”

Andrew Waugh, Founder and Director at Waugh Thistleton Architects, commented: “It’s great to see the Government taking an interest in engineered timber construction. We need Government leadership and systemic support for the use of regenerative, low carbon construction materials if we are to have any chance of reducing the impact of our industry on the planet.”

Charlie Green, co-Founder and co-CEO of TOG commented: “The Black and White Building is set to be Central London’s tallest mass timber office building. Alongside Waugh Thistleton, we have worked to reduce embodied carbon as much as possible, delivering a building that represents what future workspaces should be.

“It has never been more important to develop techniques and approaches that deliver buildings for a better world. Innovative construction processes and sustainable materials, like those employed here, will form a central part of the sector’s journey to net zero over the coming years.

“We’re really pleased that Lee Rowley, MP, visited the site today to see this evolution in practice and look forward to further engagement.”

For more information on the Confederation of Timber Industries, please visit: www.cti-timber.org.

For more information on the Waugh-Thistleton, please visit https://waughthistleton.com/

WHEN DOES TIMBER MAKE SENSE?

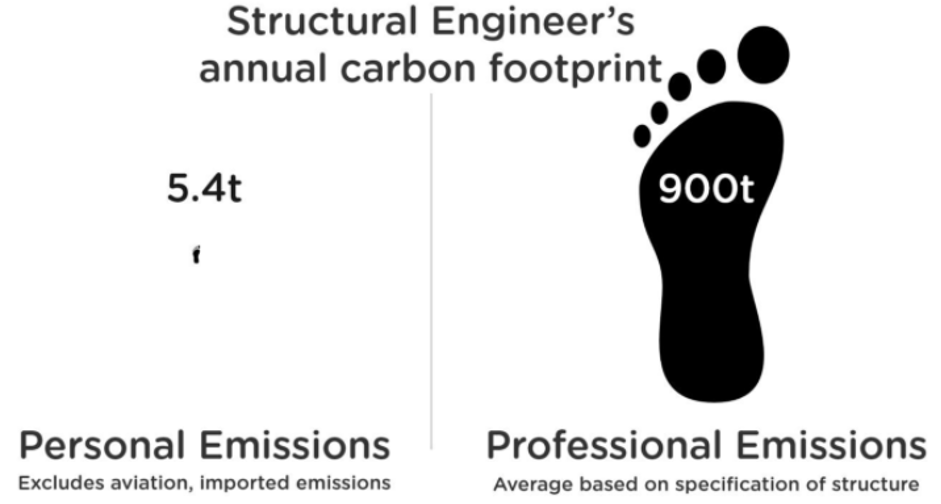

Individuals can make a limited difference to the climate challenge with their daily choices. Yes, we can all do lots of green things in our lives – we can choose not to fly, drive electric cars and eat less meat – this is of course important, but in most instances the reality is that reducing professional emissions will have the biggest impact on achieving a low-carbon society.

As a structural engineer, I am personally responsible for managing huge masses of carbon dioxide. With the strike of a pen, I could add hundreds of tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere – or make significant savings. That is why it is so crucial that those of us who specify buildings recognise the enormous importance of choosing lower-carbon solutions where possible.

Professional responsibility

Currently, the construction industry represents around 10% of total UK carbon emissions and directly contributes to a further 47%. As a result, the industry finds itself in a position of great accountability and influence with regards to the nation’s climate change efforts.

Those who design buildings and the structural engineers who determine the frame type have a huge responsibility within the construction industry. Typically, a UK structural engineer’s professional carbon footprint is around 160 times their personal carbon footprint for scope 1 and 2 emissions.

While the industry is taking steps to develop more sustainable working practices, there is a corresponding growth in demand for more sustainable development options from employers and investors and the industry needs to respond to that demand.

Enhanced public awareness of climate change, including a growing understanding of the economic risks it poses, has caused environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations to rise up corporate agendas. This has resulted in a shift in perception, where ESG is no longer considered a risk to be managed, but rather is a significant driver that is informing company strategy for long-term growth. Traditional barriers to the adoption of more sustainable development, including perceived higher costs and a general lack of awareness, are being outweighed by the increasing importance of ESG in investment and procurement decisions.

Carbon sequestration

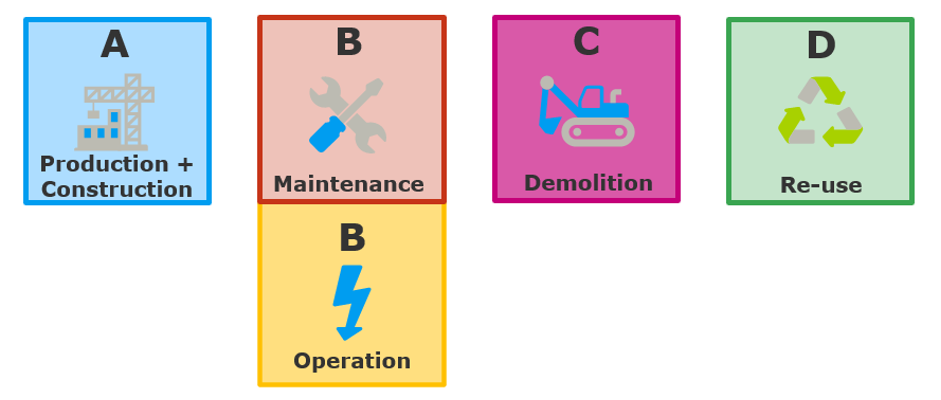

As we know, when trees grow they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere locking it away as carbon in the cells of the tree. The reporting of this carbon sequestration is often a source of debate with potential confusion and inconsistency. This often stems around when the carbon sequestration is considered. To help demystify this life cycle analysis can be used which breaks a product’s life cycle in stages. The standard used for this, BS EN 15978, can be broadly broken down into the following modules.

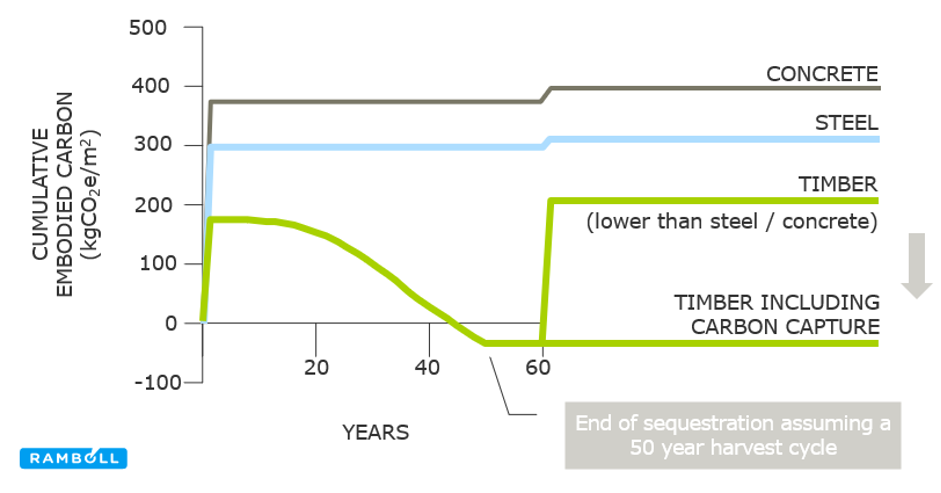

Module A dominates the life cycle emissions, particularly as we see decarbonisation in the operational aspects found in module B. Steel and concrete require a high-energy production process, but energy consumption for timber is also significant due to the harvesting, drying and sawing. Confusion with timber occurs as the amount of carbon stored within wood can be greater than the module A emissions and in some reporting is quoted as immediately carbon negative. This approach would mean that using timber excessively in a building is better for the environment – this is obviously not the case.

There are positives to sequestering atmospheric carbon within long-term timber projects as they act as a carbon sink which is beneficial to the climate. For example, over a 50-year harvest cycle in a managed forest a new tree(s), that has replaced the harvested tree, grows large and sequesters carbon from the atmosphere thereby achieving a carbon negative position. After 60 years of the building’s use, carbon is potentially released back into the atmosphere as the building is either sent to a landfill or burnt in a biomass boiler.

However, in 60 years, it could be appropriate to consider that carbon capture technologies will mean that no further carbon is emitted at the end of the life of the building. Consequently, the timber building remains carbon negative due to the carbon sink of the replacement tree(s) – steel or concrete cannot do this. It should also be noted that an efficient timber design, one which has reasonable grids and optimised design, typically has a lower embodied carbon than either steel or concrete buildings.

Accounting for sequestered carbon is a significantly debated subject, and there is much confusion and inconsistency surrounding it. Reporting sequestration alongside the reported figures of module A or a negative emission can generate the belief that using timber in excess is beneficial to the atmosphere. However when designed efficiently timber frames can be a much better option than steel or concrete frames.

At Ramboll we present our carbon figures in a clear and transparent manner so that clients can make informed decisions about the carbon impact of their projects.

At this point in time, timber currently can offer a lower carbon solution than either concrete or steel with timber having the opportunity to be carbon negative over a 50-year cycle.

If we specify and construct more timber buildings, this will buy us time against climate change to allow technologies to develop to an appropriate level until we can potentially utilise permanent carbon storage technologies or the expected lowering of embodied carbon of concrete and steel in the future.

Currently, timber is an incredibly effective and sustainable building material. However, it is equally important to understand that there isn’t an infinite supply, so attention must be paid to ethical forestry and timber sourcing to safeguard the future of timber as a material.

We currently have the understanding and tools to rationalise our design decisions with respect to the embodied carbon and, for now, timber buildings certainly form part of the solution in addressing the climate crisis.

For more information please visit www.ramboll.com

The model for a sustainable future

The Government’s ambition to achieve Net Zero status by 2050 may leave many assuming that there is ample time to adjust our behaviours in order to make this a reality. However, the fact of the matter is that we must act now and pursue environmentally friendly processes at every opportunity to stand any chance of attaining this goal. Adopting and implementing a circular economy approach is one means of doing just that, as explained by Andrew Carpenter, Chief Executive of the Structural Timber Association.

Before we can begin to discuss the circular economy, it is important to first understand the concept of a linear economy. For decades now, society at large has acted as a linear economy, following a ‘take, make and dispose’ pattern. In essence, raw materials are harvested from the earth, these materials are then processed and manufactured into products, and at the end of their life cycle they are thrown away by the consumer. For obvious reasons, this cannot be considered a sustainable model, as:

- The finite non-renewable resources within the earth are rapidly running low.

- Gathering and processing raw materials requires a vast amount of energy.

- An increasing number of landfill sites are required to store old and used products.

It should be clear then, that drastic action must be taken as we cannot continue in this manner.

A circular economy, unlike a linear economy, seeks to eliminate as much waste as possible following a product’s lifecycle. The model follows a cyclical approach. High percentages of recycled content and lesser amounts of raw materials are used to manufacture products and goods. Following their use by the consumer, these goods should be recycled almost entirely and used to manufacturer future products. If we look towards nature, no ‘life cycle’ will be found that demonstrates a linear economy, the human species is the only example to have adopted the approach. The critical environmental issues that we face today are the consequence of years of our own actions, acting as a linear economy.

However, by adopting a circular economy, we can counter each step of a linear economy system. Less raw materials will be needed to produce goods, the energy required in manufacturing will be decreased, and the resultant waste sent to land fill will diminish. We are now seeing companies beginning to adjust their processes to work in line with a circular economy approach, although, if we are really to tackle the environmental threats facing our planet, more must adopt change, and fast.

As we are all aware, the construction sector is a massive contributor to CO2 emissions and should therefore be making the utmost efforts to change this. Timber naturally fits as part of a circular economy, as it is the only truly renewable resource we possess for building purposes. Following its use, timber can of course be recycled. However, because in some instances timber is burnt following its use, some critics argue that it is more damaging than good – this is not true.

It is important that we are aware that for every tree harvested, five more are planted. Therefore, as those five trees grow, the carbon that they sequestrate more than makes up for the carbon produced through the burning of timber. Furthermore, the energy produced by burning timber is not wasted, as it is used to power our homes, schools, transportation, etc.

We believe that any hope for the construction sectors success in adopting a circular economy system lies in the use of timber.

It is very apparent that society cannot continue to follow a linear approach. The repercussions caused by decades of doing so are now being realised, with the environmental crisis we face today set only to get worse if we do not change. We believe that adopting a circular economy in how we manufacture new goods, deal with used products and – most importantly – build the places where we live, work and play, is a necessity for combatting the climate threat and achieving Net Zero status by 2050. We must act now.

For more information about the Structural Timber Association please visit www.structuraltimber.co.uk

Timber industry to make its case at COP26

In our latest Time for Timber podcast, Andrew Carpenter, Chief Executive of the Structural Timber Association, sat down with Paul Brannen, Director Public Affairs CEI-Bois & EOS, to discuss the most important event happening in 2021, COP26.

What is COP26?

The 26th Conference of the Parties, or COP26, will see the leaders of the world converge to decide how best to tackle the global crisis of climate change. For these leaders, whom have supreme decision-making capabilities, finding and agreeing upon the necessary solutions to combat this threat at COP26 are crucial to turning the tides back in our favour. Meetings between leaders are frequent but once every four years, one nation hosts a larger conference spanning two weeks. For COP26, this responsibility falls to the UK, with Glasgow hosting the event commencing on November 1st and finishing on November 12th. Since the previous major Conference of the Parties, hosted by France in 2016, the targets set have not been met, making it ever the more vital that solutions are found in Glasgow.

What is the Timber industry hoping to achieve at COP26?

Regarding sources of carbon emissions, the construction sector is responsible for anywhere between 40 and 50 percent. During their conversation, Paul Brannen highlights that it is therefore the duty of the construction industry to reduce that figure, whilst expressing his belief that timber provides the key means in which to do this. Paul discusses what he calls the three S’s, those being sequestrate, store and substitute. As a tree grows, carbon within the atmosphere is captured within the tree itself, this process is known as carbon sequestration. Once a tree is felled and processed into building materials, the sequestered carbon remains stored within the wood. The production of building materials such as cement and steel are particularly high emitters of carbon, by substituting them with timber, the environmental impact of construction is immediately lessened. These are the core messages that Paul wishes to present to the politicians attending COP26. As he states, utilising timber within construction is low hanging fruit.

How are those campaigning for timber planning to grab the attention?

As Paul explains in his conversation with Andrew, COP events are a political conference and a trade exhibition hybrid. An allocated area of the event known as the ‘green zone’ offers organisations and associations an opportunity to literally set up stall, and promote themselves to politicians, journalists and general visitors. Collectively the timber industry, at a global level, have placed their bid to the British Government, expressing their desire for a space at COP26. However, as Paul details, the timber industry has big plans on how they intend to showcase what they have to offer. Currently, plans for a purpose-built timber pavilion are being put together by a well-known British architect. The aim is to incorporate various engineered timber products within its design, to demonstrate the vast number of applications that timber possesses as a building material. The belief is that this visually stunning centrepiece will draw politicians and visitors in, so that they can be educated and informed about the structural solution to climate change that is timber.

As Paul draws his input to the conversation with Andrew to a close, he says: “We have to remind ourselves that everyday hundreds of people come to this issue completely new, and they’re the people we need to think about first and foremost”. COP26 presents a fantastic opportunity for the timber industry to showcase, to the leaders of the world, the vast environmental benefits it has to offer. Why wait, the time for timber is now. To hear the entirety of Paul’s and Andrew’s discussion about COP26, you can find the full podcast here.

3 – Wood for Good

“We got ourselves into this climate mess with aviation, deforestation – even too much procreation”

The punchy slogan to Tom Heap’s new BBC Radio 4 podcast, 39 Ways to Save the Planet, a bubbly and optimistic take on the climate emergency we face ahead of us. In episode 3, Wood for Good, Tom explains how timber, and in particular, CLT (cross-laminated timber) can be used and harnessed as a technology used to reduce carbon emissions.

The podcast gets going as you arrive in a room with the sound of saws cutting through planks of CLT in your vicinity. Tom describes the smell and aroma of sawdust and sap, the combination of which you can nearly smell yourself. Michael Ramage, a Reader of Architecture and Engineering at Cambridge University, describes the anatomy of a typical CLT beam whilst dissecting it with a chainsaw. He then explains his passion for the new material by describing how it is the newest construction material in the market and its importance to the environment in the future. Michael then proceeds to demonstrate the surprising strength of CLT beams by distributing a significant weight on it using a hydraulic press. The slender beam eventually breaks, but could withstand 2 metric tonnes of force upon it, a weight comparable to that of a large car. After showing the impressive strength of CLT planks, Tom then explores the wider reach of using timber as an anti-carbon tool by delivering some absorbing facts about the environmental capacity of timber.

Timber is a sustainable and renewable material. Whilst the idea of cutting down trees to use for buildings seems like it would cause widespread deforestation, a closer look into the management of timber production reveals quite the opposite. The timber that is used in construction across Europe is sourced from purpose grown trees in managed woodlands. Using these sources, the time it takes to grow enough timber for the material to house a family of four is 7 seconds. A 300m tall skyscraper takes just 4 hours and Canada has the timber resources available to sustainably house 1 billion people. Whilst the supply of timber seems readily available already, the renewability of the material is a key feature. Three or four trees are replanted for every one cut down in well managed timber production woodlands. This actually provides an opportunity for large scale reforestation and would evolve the fight against climate change further.

However, the main selling point of using timber in construction is carbon capture. As a tree grows it sequesters carbon in the air and turns it into oxygen. Even when the tree is cut down, the carbon stored within remains in the timber. So effectively, Greensted Church in Essex, the oldest timber church in the world, has been storing carbon emissions within its oak walls from the 11th Century. That’s nearly an entire millennium of carbon storage. It is therefore key to build with timber long term. If timber was used to build our housing, schools and even more of our infrastructure in the future it really would just be a question of how much carbon we can store. We need to plan for buildings that will last not just the next 20 or 30 years, but the next few hundred and beyond.

If you enjoyed learning about timber in construction head to https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000qy43 to listen to the full podcast of Wood for Good, as well as the rest of Tom Heap’s series of 39 Ways to Save the Planet.